Advice from Isolation: Corrie Chen on ‘what I know now’

From breaking down a script to rehearsals, what to expect from the pre-production process for a director of episodic TV.

Corrie Chen on the set of Five Bedrooms (Photo: Sarah Enticknap)

Corrie Chen on the set of Five Bedrooms (Photo: Sarah Enticknap)

As we #StayHome to help combat COVID-19, members of the Australian screen sector share their career learnings in the Advice from Isolation series. Subscribe to Screen Australia’s newsletter for additions to the series.

My episodic TV directing journey thus far has been hard fought. I did more directing attachments than anyone I know, but it meant by the time I walked onto my first show, I was more than ready and probably a little too cocky. Or so I thought.

If you love television, episodic TV directing is quite simply a dream job. I have a short attention span and have been brought up with the immigrant work ethic of a shark – keep moving or you’ll die – so the pace, energy, and challenges of television making satiates a lot of my desires. It’s also a job where you are constantly living in a world of worst-case scenarios, juggling a collision of circumstances where the director is at the intersection of dreams and compromise.

I never saw myself as the most talented student at film school, but what I lacked in talent I made up for in discipline. As I look forward to what is the next stage of my career – being both a creator and a collaborator on stories that will help reset the Australian narrative – I will always think fondly back on this episodic TV directing chapter as the one that shaped my process and made me stand up for my own ability.

Here is an abbreviated snapshot into the building blocks of that process, and other things I learnt along the way.

Pre-production at a glance

The first day of pre when you are an episodic director is a strangely low-key experience. You are literally sitting in another director’s seat, and there are still traces of them in your office. The production office is humming and abuzz with problem solving for other directors, and you find yourself fighting for attention from everyone.

Often I end up hiding in my office because I’m an introvert at heart. Faux bravado is very handy. I wear a cap, as it makes me look more like a director.

I only have one thing in mind. The script. The script. The script. In an ideal world, I’ll have already read all the scripts before I start, including the director’s release of my own block, so I can really hit the ground running. What film school didn’t teach me is that there isn’t always a script that’s ready for the director. Sometimes they might not be released until the last week of pre production. But other times, like on Five Bedrooms, they are delightfully ready a month before I start. I’m a bit of an intense prepper (as my COVID-19 pantry will attest), so I’m hankering for the scripts as early as possible. Really treasure your first read, as that is the purest. I mark down where I smile, laugh, frown, or cry (once in a blue moon). This initial impulse of delight is important to remember, and to fight for when things get gnarly.

I try and get as much face time as I can with the producers and writers. This is trickier than you think because everyone is hectic, and it’s infinitely easier when the creator is also the writer. I’m more interested in having a conversation, rather than “giving notes” with an iron fist. This might mean I’m asking a lot of inane and specific questions of the script and story in an attempt to track the decisions made up to this point. I need to understand the writer’s intention for every line, to feel a script as if I wrote it. I believe a director’s job is to defend the script when it comes under attack, which it frequently does when the pressure is on. We must trust the text at every stage. As soon as people lose faith in the text, it can become a toxic rot that takes over a show.

These first few days of pre-production are where I feel the most creatively wholesome. Production realities haven’t quite sullied my mind yet and there’s a delight in sitting around with the producers, and ideally the writers as well, talking about what the show can be. It’s very important to keep this communication channel open and to be as honest as possible to push a script to be its best. A producer once told me I’m the most glass half empty person she’s ever met. I’m not sure if it’s a compliment, but I wear it as a badge of honour. I find the most satisfying process has been one where the truly creative producers have pushed me. I love being proved wrong (don’t believe the rumours) and I never want to have the best idea in the room.

Breaking down a script

As a starting point, I look for references from other shows and films to boost my emotional literacy. The key here is emotion – what other stories have felt similar, rather than direct plot or visual reference (which is my next step). On Wentworth I watched Steve McQueen and Lynne Ramsay. On Five Bedrooms I watched Sofia Coppola and Spike Jonze. The director is a vessel for empathy, so I’m after triggers that make me feel something – anything – that are similar to what I believe the scripts want me to feel.

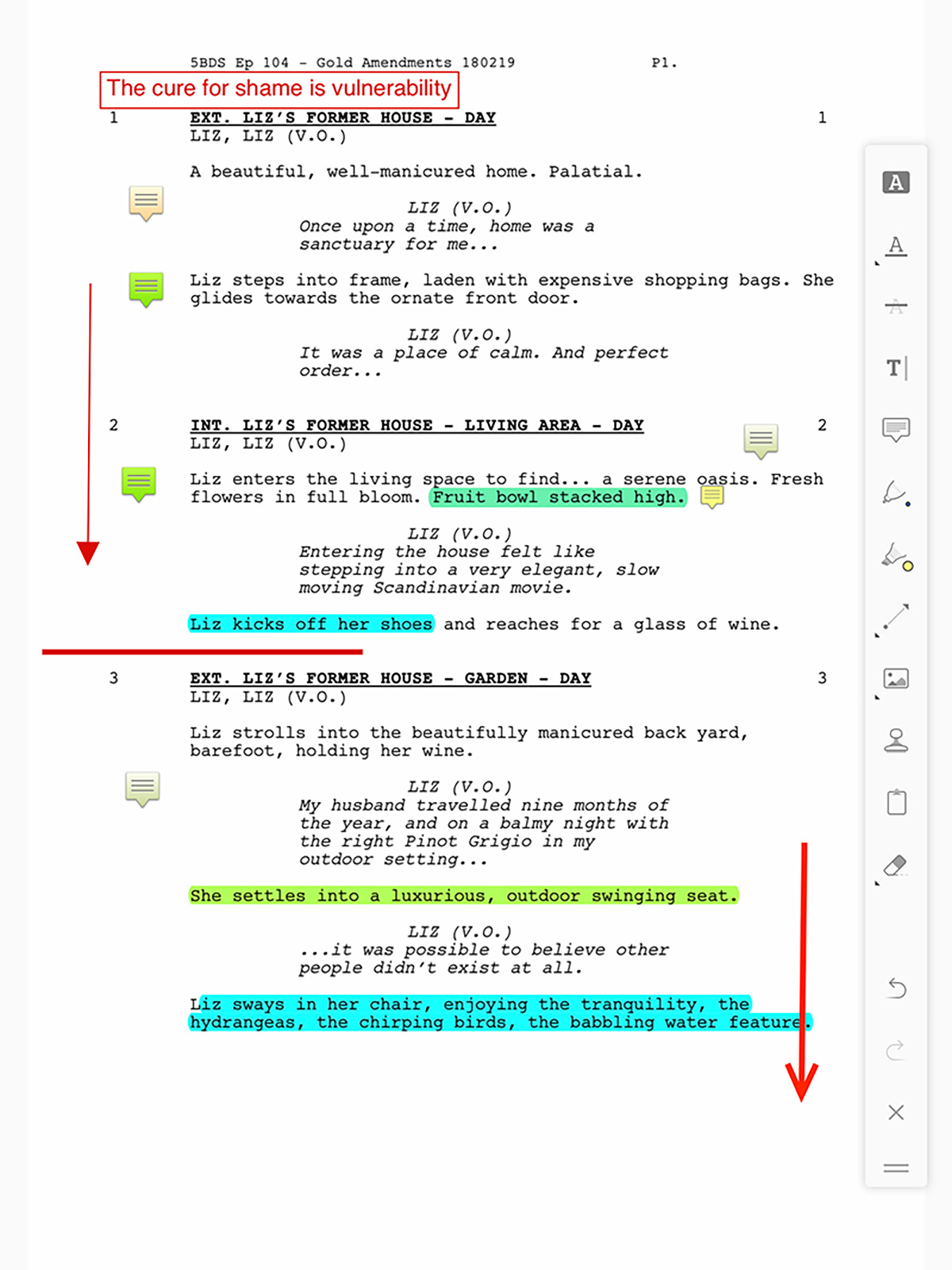

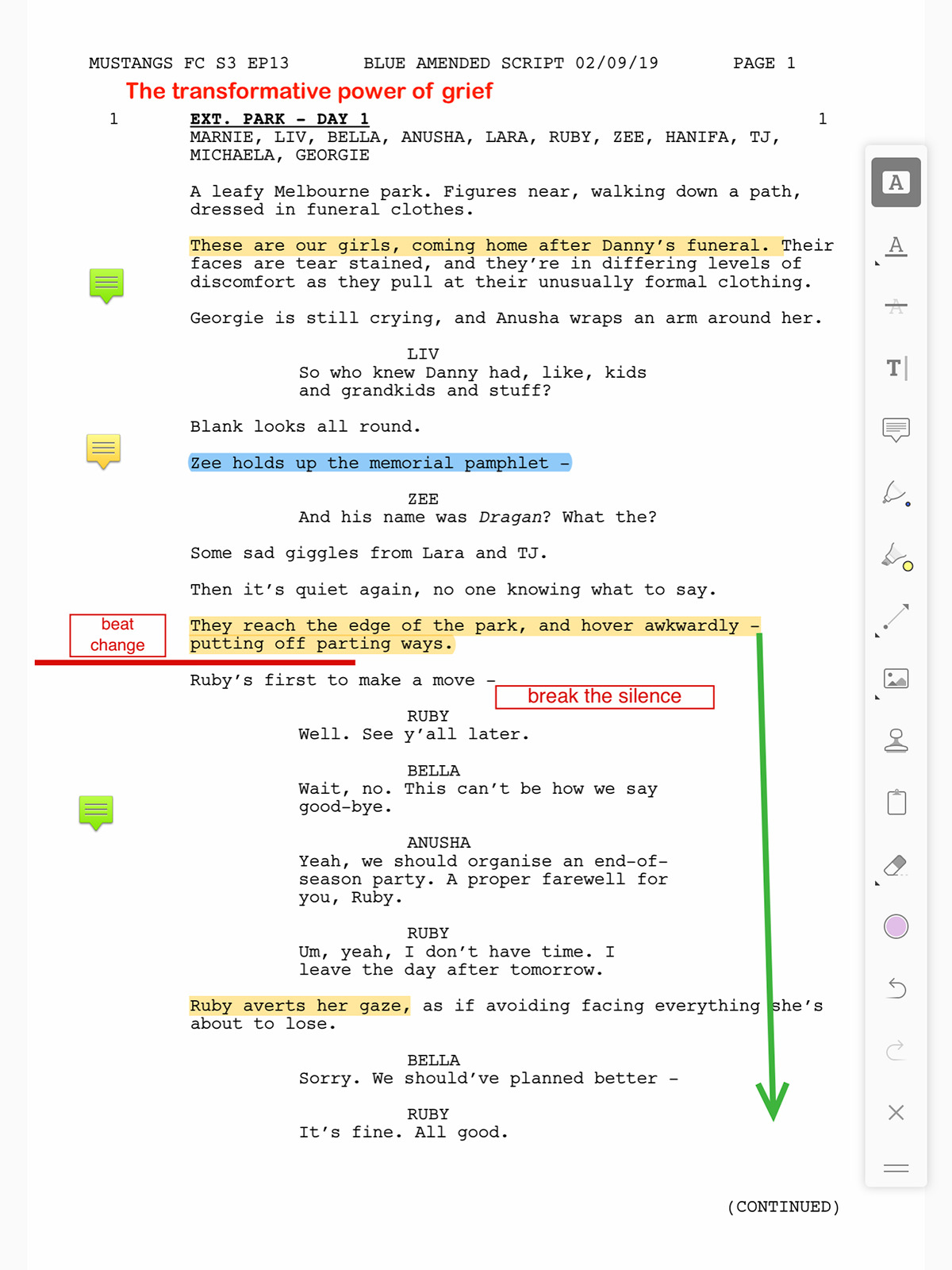

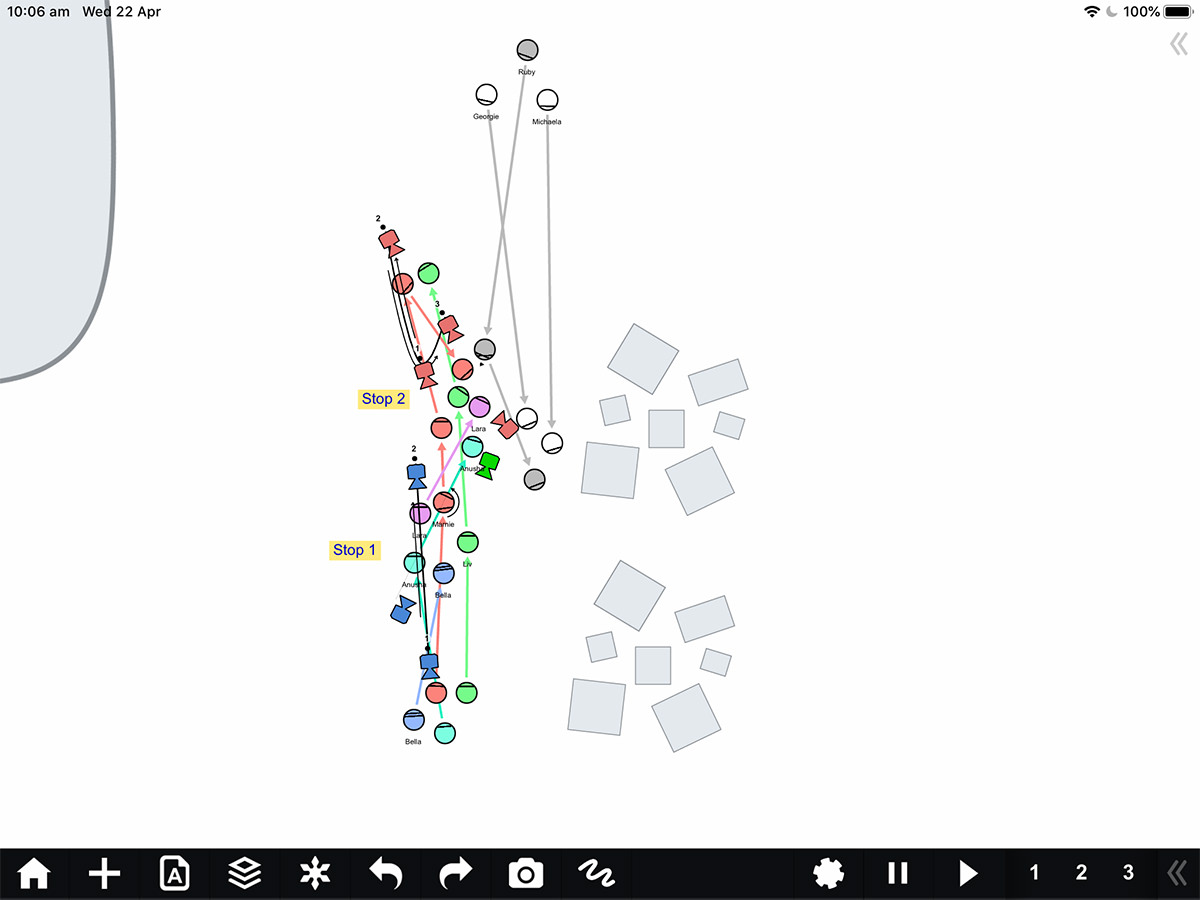

Breaking down the script is an evolving process that never stops until wrap. I work paperless on set so I use Scriptation, which is an effective program that will transfer your annotated notes across amendments, of which there are often many. I start with identifying shifts in emotional beats – I tend to block on the beat change – and what I anticipate will be performance shifts in character. This can be quite specific, and I’ve learnt to use rehearsal time to explain my process to actors. I have different coloured notes for different departments (green for shots, yellow for blocking, blue for Prod design etc - see below for reference). I write sentences for myself in bold as reminders of what I believe an episode is about – this is what I lean on when I have to make fast decisions under the pump.

Five Bedrooms script

Five Bedrooms script

Mustangs FC script

Mustangs FC script

The page turn is a meeting with all of the HOD’s and production when you talk through what your “vision” is for every scene and the problems are flushed out. I did not learn this at film school or on any of my attachments, and at my first page turn I honestly felt like I left my body from nerves, as I felt so unsure about what I was doing. I really love them now; it’s a very helpful if not painful exercise and one of the few times in pre you have everyone in the room together.

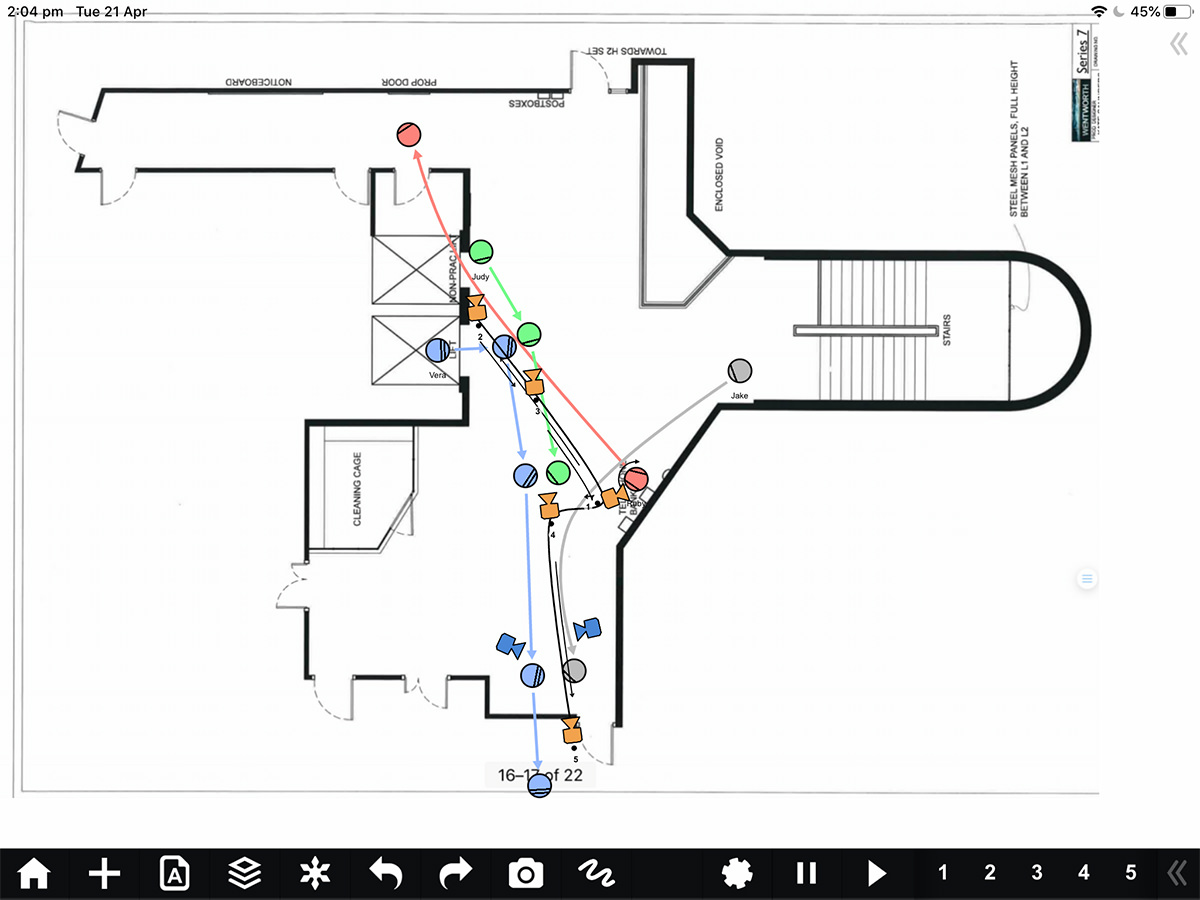

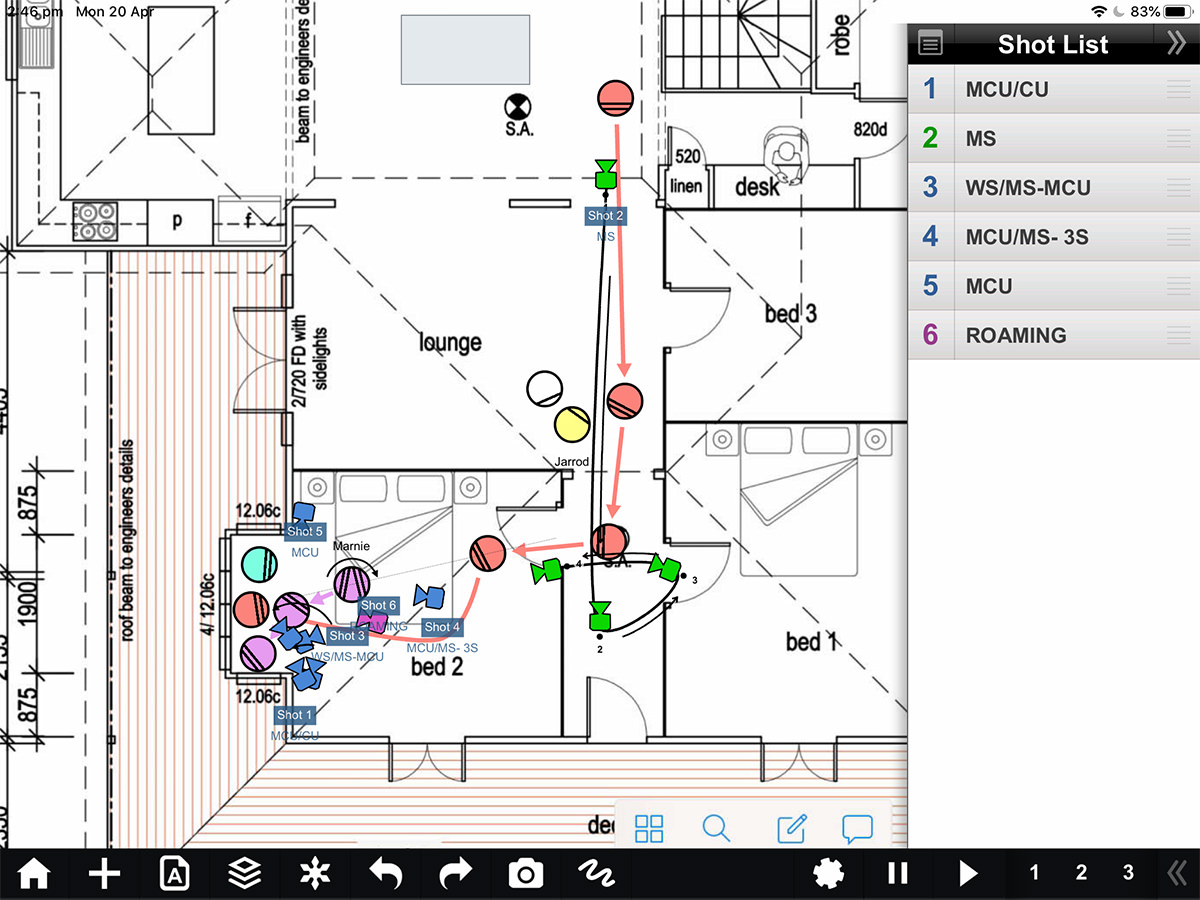

Research and plan YOUR blocking

Whatever spare moment I have, I visit sets / locations as much as possible, working off mud maps I’ve gotten from the art department. I am an extreme forecaster, and I like to be prepared, so I tend to floor plan and shot list every scene in Shot Designer. I will physically move through the scripted action as the character to see if it feels natural, and physically stand where I want the camera to go. I really take my time, and will spend my weekends on it, as it’s essentially my blueprint on set. Of course, the dream shot list will often not work out or evolves once you work with actors and the DOP, but being prepared helps with my anxiety. My stress levels are often quite high during this time as I see how complex some scenes are in relation to how much time I actually have to shoot it. I combat my stress by watching groundhogs and wombats chomp vegetables on Instagram. I also do this on set. It’s very soothing. Figuring out what quickly calms my nervous system has been a crucial discovery.

Wentworth blocking

Wentworth blocking

Homecoming Queens blocking

Homecoming Queens blocking

Before directing television, I had never directed a scene with more than three people speaking, let alone moving. These scenes are essentially a director’s bread and butter, and to me it’s about shapes and rhythm. On Five Bedrooms, I had lengthy, seated group scenes coming at me from all directions. On Mustangs FC it was gaggles of teen girls, and I would watch how they naturally formed at lunchtime to get ideas for blocking shapes. Consider where you feel the cuts might go and identify the key eyelines based on where you think the drama is in the scene. I remember I used to scoff at the idea of coverage and eyelines as “boring”, and now I know it’s only boring if the director makes it stagnant. The Social Network is something I revisit frequently for Fincher’s use of eyelines and coverage, when he chooses to over cover or under cover.

Mustangs FC blocking

Mustangs FC blocking

If I have any criticism for the current TV process, it’s that I wish there were style meetings that had all of the directors there. Part of my personal process is watching the rushes of the set-up director – on my first one-hour drama Sisters, I watched every single take of Emma Freeman’s. It felt like a personal film school on coverage and performance. You learn what to do, what not to do, and get a sense of how a set feels on screen. And that is one of the key things for episodic directing – have respect for the director before you. It’s an incredibly lonely job, and I’ve learnt to cherish the community of having other directors in the same story world.

Collaboration is key

Starting a new show, I always feel like the new kid at school, starting in the final month of year 12 – everyone knows each other quite intimately, with a lot of warmth and anecdotes, and there I am trying to find someone to sit with at lunch. The most important skill I’ve learnt is over this time is my ability to collaborate. Australian crews are amazing technicians. One of the best things about this job is that you are constantly working with new people, and discovering new creative relationships that push you to be better.

1st ADs become my protector, my cheerleader, but also give me real talk. Editors are my confidant, my psych, my parent, and at times my savior. Script supervisors, standby props, camera operators, and more – you will lean on all of them, and I have been thankful on every show. As long as you don’t do overtime on Fridays, they’ll love you back.

Unless you are authoring the show (e.g. as set-up director), the day of the tech recce is the only time you get with your DOP before the shoot (and sometimes not even that). You walk through every location and you roughly describe any special blocking and shots you might want to do. This is something I found most challenging when I first started episodic television. Film school taught me to include the DOP in my shot listing as much as possible, meaning pre-production is often spent hand in hand with my DOP, who I’m often already very close to. In the TV world I’ve had to quickly learn clarity in my vocabulary to describe visuals to a stranger. Part of the process is to figure out a shared language between the two of you – a close up can mean very different things to different people. This part is fun, there’s an incredible wealth of experience in Australian DOPs and I love hearing war stories.

Corrie Chen on the set of Five Bedrooms with actors Stephen Peacocke and Roy Joseph (Photo: Sarah Enticknap)

Corrie Chen on the set of Five Bedrooms with actors Stephen Peacocke and Roy Joseph (Photo: Sarah Enticknap)

Television is nothing if not performance driven. My film school education saw me working with largely non-actors or kids, relying a lot on lived experience. The first time I walked into rehearsals with established actors, I had no idea what to expect and was incredibly overwhelmed. Every director is different, but I’ve learnt to use it as a chance to workshop with the actors in depth about their character arc over my episodes, in conjunction with what we both perceive to be the series character arc. Again, it’s about discovering that shared language. Be open, and be vulnerable. It’s a time to flush out any moments or scenes you are both unsure about, and emotional inconsistencies within dialogue and action. On something with a large talented cast like Wentworth, rehearsals can take up over a week, and you need every minute of it. Like everything else in pre, these conversations ultimately save you a lot of time on set. I’ll walk out with a lot of feedback and ideas, and then feed these conversations back to the writers for amendments.

Without a doubt, all of these experiences have made me a better director. It’s a job that can feel masochistic at times, but I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.

What to read next

If you’re learning in isolation, we’ve put together a list of some Screen News resources to get you started.

15 Apr 2020

Georgia Hing