Advice from Isolation: Fiona Donovan demystifies the art department

The production designer on A Place to Call Home, Frayed and upcoming Back to the Rafters breaks down some key things to know about the art department.

Frayed, Fiona Donovan, A Place to Call Home

Frayed, Fiona Donovan, A Place to Call Home

As we #StayHome to help combat COVID-19, members of the Australian screen sector share their career learnings in the Advice from Isolation series. Subscribe to Screen Australia’s newsletter for additions to the series.

THE PATH TO PRODUCTION DESIGN

After finishing secondary school I studied architecture at Canberra University, but after graduation moved across to NIDA to study Theatre Design. I was really lucky to work with Janet Patterson (Bright Star, Holy Smoke) and Roger Ford (The Dressmaker, Peter Rabbit) in my second year, and in my third year did an attachment with Roger. He suggested I apply for work at the ABC and again I was lucky: I must have been one of the last people to get in before the ABC stopped hiring design assistants. I worked on Wildside, Playschool, Fallen Angels and the last series of Mr Squiggle with Norman Hetherington, which was just incredible. I decided to shift over to film; I started out at the bottom as a runner and art department assistant and worked my way up. I did some buying, drafting, and set design on a few large films like Red Planet (2000) and art directed some TV including Young Lions (2002). I kept plugging away and was on Eucalyptus (the 2005 Russell Crowe/Nicole Kidman feature directed by Jocelyn Moorhouse), which fell over at the last minute. That was a bit traumatic so I went to the ABC to design Playschool. I loved it so much I ended up staying for nine years. ABC shows worked on eight month contracts, in the break over Christmas I would go up to the Gold Coast and have fun drawing up sets for Big Brother. I picked up a lot of other work here and there and it was these years that started me approaching every new project with the question “what can I learn out of this?” How the designer approached a problem, how people in the department were managed, or how the main creatives on the production related to each other. I was always thinking, and I still do, “what can I do to make it more streamlined, more inclusive, truer to the original vision?” Basically how to make it better on every level.

In 2011, Tim Ferrier asked me to art direct on Crownies, I was ready to move on from the ABC, so I jumped at the opportunity. When he left after pre-production to do Wild Boys, I continued on the series as the designer for all 22 episodes. I worked with Tim again as art director on Love Child and then A Place to Call Home, which was cancelled by Channel 7 after two series. When Fox brought it back, Tim had moved on, but I really felt attached to the show so I went for the role of designer. I was interviewed and it was quite a rigorous process, but I got the job. I designed from series three to series six, winning an AACTA award for series five, and that has kind of launched me into being a production designer. Since then I’ve designed Frayed for the ABC, Between Two Worlds for Channel 7, and an upcoming independent feature Rising Wolf. I was just working on Back to the Rafters for Channel 7, which is now in hiatus because of COVID-19.

Fiona Donovan on location (image supplied by author)

THE WORLD OF YOUR STORY

The art department is responsible for everything that appears on screen outside of the actors and what they're wearing. So it’s not hair, make-up, or costume. But cars, trees, fences, houses, even the bins: that’s all art department. If you were inside a room, it's the walls, furniture, light fittings, and curtains. If the character has a mobile phone they pick up, then that will be a prop, not costume, and therefore part of art department. Some props will be “prac”, for practical, meaning they actually have to work. So a prac baby's bottle is one you could actually use safely to feed a baby. You have to think about not just whether it’s functional but also whether it’s legal and safe to use. A non-prac prop just has to look right but never gets used: for the baby there might be a pile of nappies in the shot, but hopefully they don’t actually get used. Sometimes you'll have things that look like they can be used, but actually can't; for example taps that aren’t connected to mains pipes, so that you might have to hook up to a hose to film water running out. So there's a lot of illusion that goes on, because if you were to build a house for real - to do all the plumbing and electrics – it would be too expensive. On the other hand, sometimes for a set that's standing for a long time (e.g. on a long running series), it can just be easier to make things like light switches or sockets “prac”, so you might get an electrician in to wire it all up and make it safe.

The art department is giving the show a visual scaffold to hold the story together. A really great cinematographer is going to make it look beautiful on the screen, but if an audience sees something in the “world” of the show that isn’t right, it breaks the suspension of disbelief. So without the right detail, you can lose the audience. Production values, particularly on TV, are getting higher and audiences are becoming more sophisticated. If there’s a room and there are no light switches, or if they’re the wrong ones for the era, or they are from the wrong country, the audience will sense “something’s not right here.” Visually, there's a lot of stuff people don't realise they know. It's subconscious.

I’m writing about physical creation, which is where I’ve mostly worked, but the visual world of a screen production now includes more and more VFX, which has large elements of crossover and collaboration with the art department. The same principles apply to VFX.

PRODUCTION DESIGNER VS ART DIRECTOR

I think of the production designer as being the architect and the art director as the project manager of the department. It’s a completely different mindset. The production designer will say “I want it to be blue” and the art director has to respond with: “What kind of blue? When do we need it by? How much is it going to cost? Who's going to do it? And are you really sure you want it to be blue?”

An art director is a nuts and bolts person. They're very practical. They are looking at allocating limited money where they are going get the most bang for buck. As an art director you have to build your department to be very agile because if someone gets sick, or if it rains and you have to go wet weather, you need to be always thinking about what if, what if, what if. A designer also does that to some extent, but they need to think more about what they want the end effect to be and less about the nuts and bolts of how to achieve it. If they think too hard about how, they’ll never get there. You can't do both. You have to have a freedom in designing that you can't have if you're also project managing. You have to trust that your art director will find the best way to achieve what you want. So when I first stepped up into production designing, I had to let go of my practical art director instincts and allow myself to just think more about what I wanted the world to be.

TALK TO US EARLY

If you’re a director, producer, writer or showrunner, get your Production Designer in early and talk to them. Start the conversation. I had a great experience with the show creator Bevan Lee and script producer Katherine Thompson on A Place to Call Home, and they were constantly talking to me about their ideas. As a writer or director, what you're thinking about is not what the production designer is thinking about. Especially if, as a creator, you aren't quite sure what you want visually, a production designer can offer ideas and help guide the look of the project based on their research. The art department has a lot of knowledge around expressing story, characters and themes in a visual way.

The other reason to start discussions early is that physical things like props take time. On A Place to Call Home, Nyree Winter did an incredible job as our props mistress: because our story was set in the 50s everything had to be made from scratch or found online or in vintage shops. When you buy something from a vintage shop, those objects are now 60+ years old, so you’ve then got to make it look new again. This takes even more time and it’s often not straightforward. For example, there was a scene in A Place to Call Home where Elizabeth (Noni Hazlehurst) is eating something after a meal and she cuts Sir Richard (Mark Lee) on the hand with her knife. We had to work out what she was eating (fruit), what the right knife would be for someone in her social position in the 1950s, and then in reality would that knife have been sharp enough to cut his hand (it could have been). Then we had to make rubber knives that weren’t actually dangerous, and ones that had blood come out of them for the effect. So a seemingly small detail can't just happen overnight.

THE PROCESS

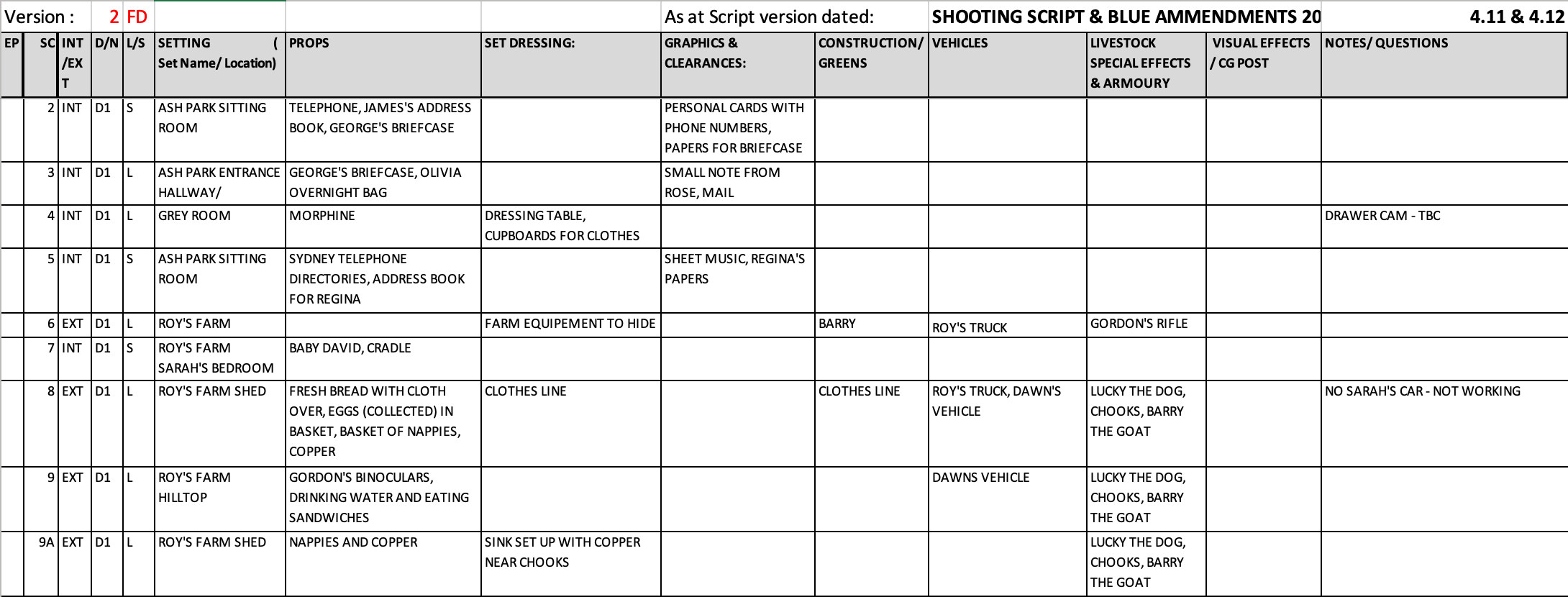

I’ll start every job with the script. The first read is just to see what happens, but from there I’m re-reading it for the emotional beats and identifying practical elements. I'll start looking for locations and drawing up sets and doing research. I'll initially do a set breakdown to work out how many and what sets are needed, and then I'll do a proper full breakdown where I write out the scene number, interior, exterior, location, the actors, the props and the dressing. And then depending on the show, the animals, vehicles, special effects and visual effects. You get to know the script intimately, and as a production designer you’ll have ongoing discussions around breaking down the script with the art director to work out where the budget needs to go.

Set breakdown

Set breakdown

From there, you start talking details with the other key creatives: the director, producers, DOP, costume designer and makeup designer. Often it's a very collaborative process. You’re not by any means working in a vacuum when you're a production designer. Early in pre-production on Frayed we had a day in a room with the creator of the show Sarah Kendall, the director, the DOP, the costume designer, the hair and makeup designer, the creative producer and me. We all came together to show Sarah our ideas and the look of the series just crystallised in that one day. Very quickly we were on the same page and from that we created a style “bible”, which is a printable reference for visual tone not just for the art department, but the whole crew, that can be referred to throughout the production.

Drawn up sketch of restaurant vs restaurant set

Drawn up sketch of restaurant vs restaurant set

ELVES IN THE NIGHT

A lot of what the art department does is unseen because it has to be ready to go when everyone shows up for filming. Every day, we can move one or two houses worth of stuff, and when the crew turn up, it's perfect and ready to go. But it takes a lot of the elves working overnight to make it all happen. Australian art director/production designer Jacinta Leong works on a lot of the big studio movies and she does time lapse films of the set builds. You can watch them online (Alien: Covenant, The Wolverine, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales and Pacific Rim: Uprising, which we worked together on) and they're really incredible, just to see the amount of work that goes into it. It’s weeks and sometimes months of prep work for something that will be filmed over days and on screen for minutes or seconds.

GROWING IDEAS WITH DIRECTORS

Early discussions in pre-production with directors are often speculative “what if” and “how about” conversations. It’s better when they’re not framed as a shopping list (e.g. “I need a black Mercedes and a three-story house with a pool”) but as questions about the nature of the world we are creating, and the feelings we want to convey. In particular, what are the pivotal moments in the story and how do we support them visually? Sometimes as designer you can contribute quite a lot. For example, for the very final episode of A Place to Call Home, I was working with director Catherine Miller. We were thinking about how to present the ending, and I had an idea in reading the script that it could take place over a year, shown through the passage of seasons. It really sat well with the way the script was written, from spring including the birth of a child and a big Christening and so on through a New Years Eve party in summer, leaving home in autumn and the final ending in winter. Visually it just tied the episode together. It was just a thought and a couple of images, but I took it to Catherine and said ‘what do you think?’ And it became this little idea that we grew together. And every director I’ve worked with, I might come give them little seeds of an idea and then they add onto that, and through these conversations it grows into something bigger.

A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home

CAMERA TESTS MATTER

The DOP and production designer should have a relationship of mutual support. The choices the art department makes around light sources and reflections and colours can have a huge impact on photography: for example the colour of curtains on a window or a lampshade will directly affect the colour of the light used to light an actor’s face in close-up. On Frayed I worked with the amazing DOP Matt Temple. He and I had a fantastic conversation in pre-production through exchanging books, for example the photography Suburbia by Warren Kirk, which became inspiration for the tone and feel of Australia in the late 1980s. It might have seemed like we never talked to each other once we were filming, but it was because we had done all the work at the beginning, in pre. And I find that’s the case with most DOPs.

The initial camera tests are very important to me. I have big boards painted up of all the colours. Even if I don't use them, I can see what happens to a colour when the DOP lights it the way they're going to shoot and light the production. And then I can also see what the actors look like and how the how the colours change with the LUT (grading). For Frayed, we had two LUTS: one for the UK and one for Australia. The UK was moody, washed-out grey blues, and Australia was sunny, bright almost blown-out light. We then reflected this in choice of sets and props.

Frayed UK vs Australia LUTS

Frayed UK vs Australia LUTS

LOCATION MANAGER

Location Managers are incredibly important to making everything run smoothly. Depending on the way the show is setup, often the location manager starts before the production designer but getting the production designer involved as early as possible can save time and money down the track. As locations are proposed, the designer can assess how much work and budget is needed for each. For a production designer, there is nothing quite like the hours spent in the car with the location manager driving around looking for locations. I've worked with some amazing people, like Phillip Roope, Ed Donovan, Lisa Scope and Carl Wood. Their knowledge of Sydney and beyond, and their ability to think of solutions out left of field, is incredible.

AND MUCH MORE…

I hope this has demystified a small part of the jobs of the elves who magically transform spaces into other worlds. There are many more roles I haven’t covered: set decorator, props master/mistress, art department co-ordinator, graphic designer, buyer, dresser, specific props construction as well as greens, swing gang, plasterers, armourers, SFX technicians, animal wranglers, vehicle wranglers and more. For those interested, a great online resource to see the crew requirements for art department, costume, hair and makeup is the Australian Production Design Guild Manual for Screen Design Practice. Otherwise ask your friendly production designer or contact one through the APDG.

What to read next

From breaking down a script to rehearsals, what to expect from the pre-production process for a director of episodic TV.

23 Apr 2020

Corrie Chen