After 30 or so years in the industry, Carolyn Constantine ACS received her letters in 2017, becoming the 11th woman to do so.

“I probably should have gone for it earlier,” she admitted, but she wanted to make sure the body of work she presented to the judging panel was the best reflection of her capability as a cinematographer. “And I really felt like it took me until to that point. When I did [ABC TV’s] Pulse and I got to shoot the two last episodes, and I shot my own documentary [Madhattan], I felt like they presented opportunities to create work that I felt proud and confident enough to include.

Carolyn Constantine ACS received her ‘letters’ in 2017, and is one of only 15 women to do so

“It just took a long time to get the opportunities to do the work that I felt like I wanted to present to my peers. It took a lot longer than I thought it would.”

It’s probably the biggest hurdle Constantine sees – the lack of opportunity to prove yourself. And she feels like one of the lucky ones. She started out as an assistant to Addis, worked as DOP (Director of Photography) on Cate Shortland’s early films including the short Pentuphouse and feature Somersault (as 2nd unit DOP), and was mentored by the late Andrew Lesnie ACS ASC as he shot Lord of the Rings.

She began working in the industry when the cameras were still heavy – one of the reasons she’s sceptical physical strength was ever a valid excuse for the lack of female cinematographers.

“I mean a woman can carry a baby can't they? A baby's heavier than a camera,” she says.

She recently was the 2nd DOP on the forthcoming Channel Seven drama Australian Gangster alongside the main cinematographer Garry Phillips ACS. “And that was all handheld, every day for weeks and months and it wasn't a problem,” she says.

Constantine has trodden the traditional path, working her way up through the various camera roles, but it’s breaking into becoming a DOP that was the toughest transition.

“I think the thing is there's a lot of women that study cinematography and want to be cinematographers and there's a lot of camera assistants and focus pullers. There's a few camera operators, and then there's even less DOPs. So it's this attrition rate as it goes up through the hierarchy of any film and camera department,” she says.

“And to be able to move forward, you need those opportunities. You need someone to take a bit of a risk. Success as a DP also involves in some ways taking creative risks.”

And she’s watched as a lot of her female peers left the industry out of frustration because despite their talent, no one would give them that chance to prove themselves.

Indeed if you look at the steadily decreasing number of women represented in the ACS data, the variance between the camera crew tier (15.9% women) and the cinematographer tier (6.5% women) is stark. They have 21.3% student members, and as mentioned previously AFTRS’ female graduates in the Cine strand range from 33%-44% of graduates – a trend that isn’t carried on into the industry.

FAMILY VS CAREER

Addis says starting a family and being able to afford childcare are real obstacles to women's trajectory.

She says for example you might enter the industry in your early 20s as a clapper loader, or a runner, video split operator or a camera assistant.

“If you take a conventional path then you will probably be working as an assistant for maybe 10 years. You might be starting to shoot things in the latter part of those 10 years and getting gigs that are decent,” she says.

“And at about 35, if you haven't had kids already, you [have to ask] am I going to keep going for the career? Or am I going to have kids? And can I do that and have my career?

“The thirties is crunch time for women.”

She says a lot of successful female cinematographers with children have managed thanks to a supportive partner or family network who can help when working on location, with unpredictable hours and changing schedules. “Childcare is a nightmare,” she says. But it also means if you don’t have that support system you have to make that choice: work or family.

Tania Lambert ACS on set in 2018

“And so a significant proportion of women who were maybe making their way successfully slowly up the ladder just hit that road bump and either get through it or don't,” she says.

It’s an obstacle the industry is grappling with across the board. For example, Beth Armstrong was a director’s attachment on Hacksaw Ridge – a $20K funded attachment through the ADG and Screen Australia – and she said $13K of that went to childcare for her two children so she could take on that opportunity. Meanwhile at the 2018 Screen Forever conference they introduced a crèche to help working parents attend. And on a panel at a Raising Films Australia event in late 2018 there were discussions around childcare and the Producer Offset.

While childcare is not specifically mentioned in the legislation, projects applying for the Producer Offset may be able to include the cost of childcare within the QAPE budget if it is reasonably attributable for the making of the film e.g. for cast and crew working on location away from their residence, but still within Australia.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THERE'S SUPPORT

Addis says when it comes to family, documentary is more accepting than feature film or TV drama. It’s perhaps a reason why there seems to be more representation for female cinematographers in that format.

While the focus of this piece is on feature film drama, in 2018, six of the 19 (or 32%) feature documentaries released theatrically credited a female cinematographer.

Addis says that reflects her own experience working in documentary.

“Often you're filming people and you can't just make the subjects in your film work for 10 or 14 hours in a day,” she says. “So documentary schedules actually accommodate more conventional, normal hours and hence the crew actually get to have a slightly more civilised life than when you're working on feature film or television drama.”

She says there’s also the perception that there’s less risk in documentary.

“The thing about documentaries is because they're lower budget, they're seen to be lower stakes. The crews are much smaller,” she says.

“All of those things can make for a more humane and egalitarian working environment… which is often more accepting of women. They don't have to fight so hard to actually get the jobs.”

Addis says there needs to be a push, not just for female cinematographers, but for female Heads of Departments of all varieties.

“We’ve all seen the massive turnaround that's happened because of the support that's been given to writers, producers and directors,” she says.

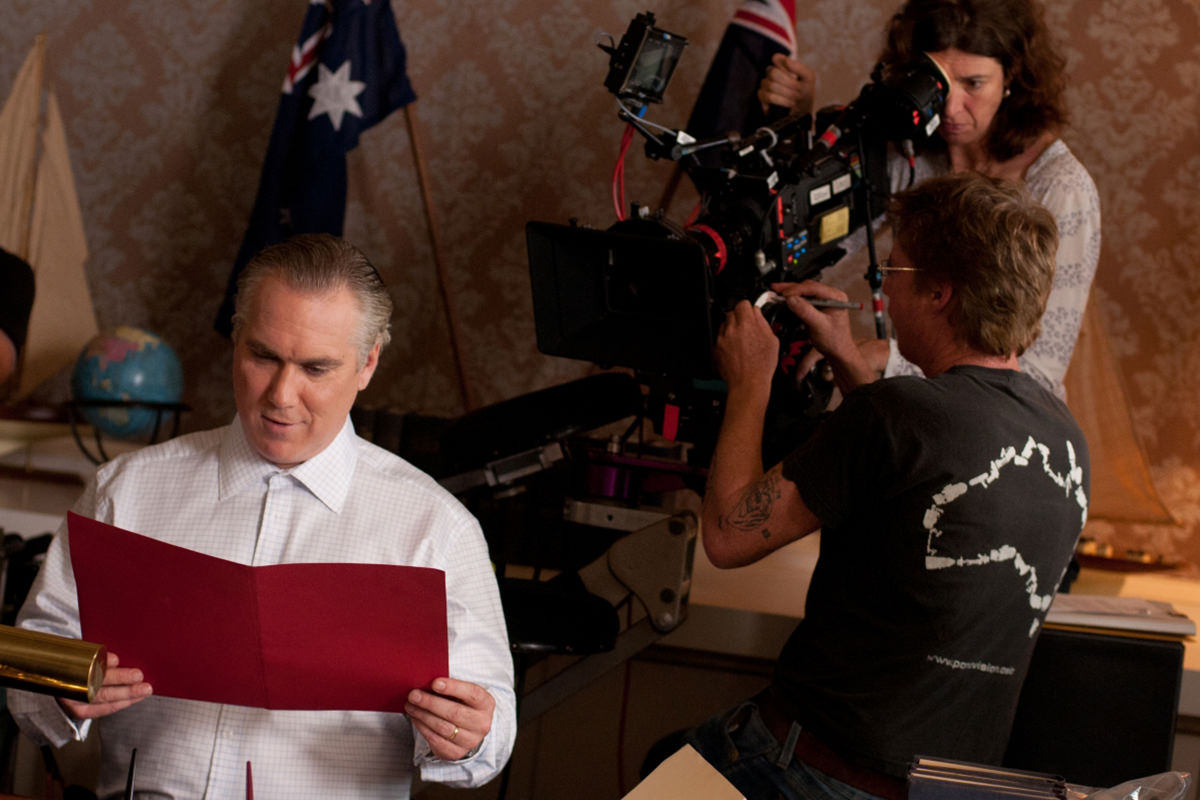

Carolyn Constantine ACS operating the camera during filming of Rake

Carolyn Constantine ACS operating the camera during filming of Rake

This is in reference to Gender Matters, and in particular the Brilliant Stories strand. While below the line roles were included in the Attachments for Women scheme, the focus of the launch was largely on Brilliant Stories, which provided one-off support to 45 successful projects that fulfilled requirements for female directors, writers, producers, or protagonists.

“We felt left out in the Gender Matters discussion and disappointed that it just stopped at those three roles. I mean it was fantastic that it happened. I just wish that it had been more comprehensive because there was so much attention, and so much oxygen was given to the discussion at that time that it was really disappointing that clearly the logic was if we look after those three areas there will be a trickle-down effect. But the trickle-down effect is always so slow, because all it takes is one person, between a director and producer, to not feel confident that a woman is able to do a serious technical role and it just won’t happen. Especially with cinematography, because if the camera's not rolling, money's just going down the drain.”

She says in the past she’s taken calls from completion guarantors asking her to describe the temperament of former female cine students up for their first feature film job. “Not what their skill set is,” she says.

“So a lot of scrutiny goes on that’s completely under the radar about heads of department. It’s quite hard to get past those hurdles because you don’t even know that they’re in front of you.”

Since Gender Matters’ launch, Attachments for Women has been expanded into an Inclusive Attachments Scheme, whereby a condition of Screen Australia production funding is to include an above or below the line attachment. The updated Enterprise guidelines have also been expanded to include below the line roles in both the Business & Ideas, and People strands.

Constantine hopes more directors and producers regardless of gender think about the diversity of their heads of department, and even in this economically tight space, people still take risks by hiring outside the box.

“If everyone just played it safe, we wouldn't actually progress as a society or creatively, we'd just stay the same and just have this status quo. It's the ones that have taken a few risks that have actually even opened the doors for women to come forward and show what they can do,” she says.

“And I think, as a head of department I am very aware then of choosing crew. If I can I'll try and make the camera department 50/50. I don't want to go the other way and employ all women. I just want to have parity and equity.”

Title image: Still from one of the episodes of Pulse shot by Carolyn Constantine ACS.

What to read next

A case study that deep dives into the representation of women in Australian animation.

15 May 2019

Caris Bizzaca